Beschreibung

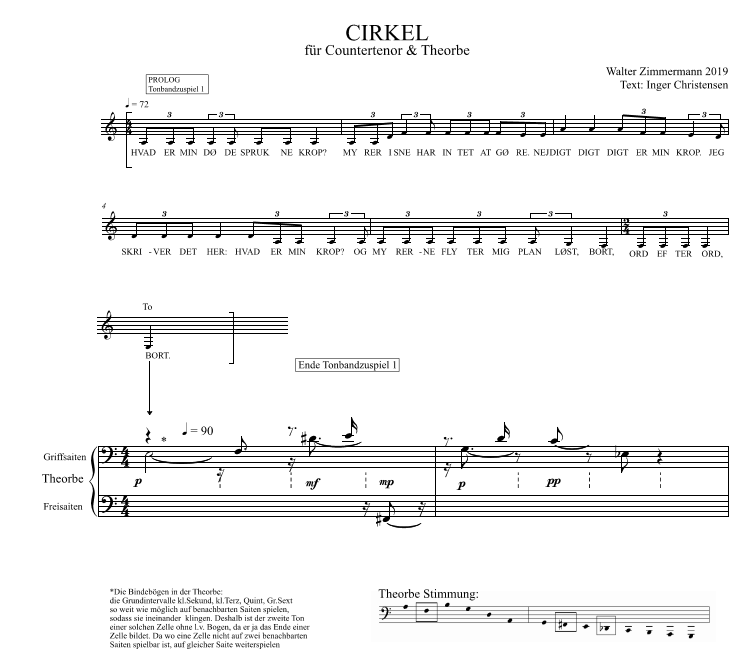

„Cirkel“ – “Kontakt” (2019)

für Countertenor und Theorbe, Tonband.

Worte, dänisch: Inger Christensen (die auch selbst singt))

„Från havets bibliotek“ – “Aus der Bibliothek des Meeres” (2006)

für Countertenor und Gambe

Worte, schwedisch: Tomas Tranströmer

„oúschabi at toufoúla” – „Gras der Kindheit“ (2006)

für Ud mit Gesang [in einer Person]

Worte, arabisch: Fuad Rifka

“Zman” – “vertont” (2007)

für Countertenor, Barockoboe und Barockvioline

Worte: Felix Philipp Ingold (Hebräische Übersetzung: Eliav Brand)

„De litanie van het oog“ – “ Die Litanei des Auges” (2006/2019)

für Countertenor, Barockflöte, Barockvioline, Ud, Gambe

Worte: niederländisch: Cees Nooteboom

“Ett Avlägset Land” “Das abgeschiedene Land” (2019)

für Countertenor, Barockoboe, Barockvioline, Ud, Gambe, Tonband.

Worte, schwedisch: Gunnar Ekelöf (der auch selbst spricht)

Ensemble Lipparella (Stockholm)

Mikael Bellini–Countertenor

Anna Lindal–Barockvioline

Kerstin Frödin–Blockflöte & Barockoboe

Louise Agnani–Viola da Gamba & Barockcello

Peter Söderberg–Laute, Oud, Theorbe

Chantbook_for_Lipparella

POSITIONEN 135

C D

Walter Zimmermann

Chantbook for Lipparella

World Edition

Bereits Walter Zimmermanns 2021erschienene Dreifach-CD Voces (Mode Records) kreist um einen wichtigen Fokus seines Komponierens: den vielschichtigen, das Gesamtwerk durchdringenden Umgang mit Gesang, mit Stimmklang, sowie mit einer als Klangrede auf zufassenden, instrumentalen Artikulation. Zimmermann befreit in seiner Musik nicht nur das Wort zum Klang, sondern inszeniert gleichwertige Verhältnismäßigkeiten zwischen instrumentalen und vokalen Bestandteilen, wobei die Musik nicht in erster Linie dazu da ist, Gesang in einer untergeordneten, bloß dienenden Rolle zu begleiten. Darüber hinaus entstehen komplexe Partnerschaften wechselseitiger Art zwischen Musik und Text, wobei unter anderem Buchstaben in Tonbuchstaben verwandelt werden.

Ähnlich wie Voces ist auch die unlängst erfolgte Veröffentlichung Chantbook for lipparella als ein multiperspektivisches „Gesangbuch“ angelegt, das den Umgang des Komponisten mit Vokalisationen exemplarisch in zehn Stücken „aufblättert“. Die Aufnahmen sind in Zusammenarbeit mit dem schwedischen, 2008 gegründeten Kammerensemble Lipparella entstanden, das zeitgenössische Musik mittels eines Instrumentariums aus der Barockzeit beziehungsweise der Renaissance (Flöte, Oboe, Laute, Violine, Viola da Gamba),

erweitert durch Gesang (Countertenor), realisiert. Für diesen Klangapparat wurden acht bereits bestehende Kompositionen Zimmer manns eingerichtet, und auf der CD mit zwei weiteren, für Lipparella neu geschriebenen Stücken ergänzt.

Anverwandlungsprozesse liegen dem Komponisten nicht fern, im Gegenteil. Unter schiedliche Modi der Übertragung spielen bei ihm seit jeher eine Rolle, seien es instrumentale Transkriptionen von Gesangsaufnahmen, oder die Übersetzung von geschriebener Sprache, von Worten, Begriffen und Sinnzusammenhängen in Musik (vgl. exemplarisch die Klavierkomposition Voces Abandonadas von 2005/2006 (Wergo) auf Basis von Sentenzen des italienisch-argentinischen Schriftstellers Antonio Porchia).

Eine zusätzliche „Kontaktaufnahme“ zwischen Sprache, Literatur und Musik ist das Einbeziehen von Rezitation, die etwa bereits in den Songs of lnnocence andExperience (1996/2004) begegnet. Dies ist auch auf der vorliegenden CD in zwei Stücken anzutreffen, beiCirkel– Kontakt (2019), wo die dänische Dichterin lnger Christensen eigene Lyrik singt, und mit dieser Vortragsart bereits die innige Verbindung von Poesie und Musik dokumentiert, sowie in Ett avlägset land

– Das abgeschiedene land (2019), eine Text-Vertonung des schwedischen Dichters Gunnar Ekelöf, dessen Stimme in dem betreffenden Stück ebenfalls zu hören ist.

Typisch für Zimmermann geht es dabei nicht um eine gewollte Verschmelzung oder herbei gezwungene Synthese, sondern er stellt der Dichtung beziehungsweise der Sprachgestaltung anderer seine eigenen, nicht selten konzeptuell bestimmten Klangfindungen zur Seite, um einSpannungsfeld aufzubauen, das auf subtile Art und Weise eine Begegnung, beziehungsweise eine Kommunikation auf „höherer Ebene“ anstoßen kann.

Der transparent wirkende, präzise, aber auch warme Klang der Barockinstrumente sowie das tiefe Verständnis Lipparellas für den künstlerischen Ansatz des Komponisten ermöglicht diese Kommunikation auf eine eindrückliche und – man kann es ruhig sagen – zauberhafte Weise. Dies heißt jedoch nicht, dass Zimmermanns Musik von Lipparella in eine ferne, vormoderne Vergangenheit rücküberführt wird, sondern sie gewinnt an aktueller Präsenz mittels der Befreiung vom spätromantischen Gewand, in dem die zeitgenössische E-Musik bis heute instrumentalhistorisch eingekleidet ist. Dies wird auch bei den Stücken deutlich, in denen avantgardistische Techniken zum Zuge kommen, zum Beispiel dem von dem US amerikanischen Maler Brice Marden inspiriertenShadows of ColdMountains I (1994),wo drei mehr oder minder unisono angelegte Stimmführungen von drei Renaissance-Blockflöten in weit ausholenden Glissando-Bewegungen ausgeführt werden, oder dem auf Basis einer grafischen Partitur entstandenen Paraklet (1995), wo eine ebenso in drei Stimmen aufgefächerte Barockvioline diffizile Flageolett-Strukturen in Form einer nahezu grenzenlos fließenden Mikrovariantenbildung auszuführen hat.

Thomas Groetz

Walter Zimmermann, A Chantbook for Lipparella, Lipparella (Louise Agnani, viola da gamba; Peter Söderberg, lute, oud, theorbo; Mikael Bellinini, countertenor; Annal Lindal, baroque violin; Kerstin Frödin, blockflute and baroque oboe), World Edition 0041

More and more recordings of Walter Zimmermann’s beguilingly enigmatic music have become available in recent years, from Nicolas Hodges’ survey of his piano music on Voces abandonadas (a series of WDR recordings from 2009, eventually released by Wergo in 2016), to the 2019 Mode reissue of the complete Lokale Musik recordings (originally released on LP in 1982), the Sonar Quartet’s Songs of Innocence & Experience, a collection of Zimmermann’s string music from 1977 to 2003 (again for Mode, released in 2020) and the retrospective gathering of his music for voices on the Voces album (also Mode, released in 2022). But this Chantbook is different, conceived not so much as a compendium, more as an album, where musical ideas flow across the ten tracks with a cumulative expressive intent.

The paradox is that this album too is a sort of retrospective, drawing together works from a period between 1994 and 2021; what makes it special, however, is that each work has been reconceived for the resources of Lipparella, a Swedish ensemble devoted to the creation of a new repertoire for Baroque instruments and countertenor. Walter Zimmermann’s collaboration with Lipparella began in 2019, the product of a chance meeting of Zimmermann and Lipparella’s Peter Söderberg at the Ultraschall festival in Berlin, but only two of the works presented here were written specifically for Lipparella. Dit, for example, was written in 1999 for ensemble recherche’s ‘In Nomine’ project. A solo string instrument, a cello in the recherche version, a viola da gamba on this album, shadows the melody of a folk song from Western New Guinea that, like John Taverner’s ‘In nomine’ melody, has a range of a ninth. It’s a breathtakingly arbitrary connection, and in this new setting it is no longer even contextualised by other ‘In nomine’ music; but it’s also breathtakingly beautiful: for a little more than two minutes voices speak to one another across time, geography and cultures.

Something similar happens on the opening track. Cirkel begins and ends with the voice of the Danish poet Inger Christiansen (1935-2009) chanting parts of her poem ‘Lys’ (1962); her intonations are diatonic, with something of the quality of a nursery rhyme, yet they frame music for countertenor and theorbo, Zimmermann’s 2019 setting of another Christiansen poem, that is much more fragmented and chromatic. ‘To sketch a spindly circle in water or air’ is how the poem begins and it is just such a spindly circle that Zimmermann’s music evokes, the complexity of his musical response apparently at odds with the assuredness of the poet’s own voice.

Different qualities of voicing are also explored in the third and fifth tracks, Gras der Kindheit and Från Hovets Bibliotek aus der Bibliothek des Meeres (both 2006), where Peter Söderberg’s oud playing and Louise Agnan’s viola da gamba playing, respectively, is combined with their singing. Both sing well but there is no doubt that this is not their day job. As Söderberg observes in the excellent liner notes that accompany the CD, his is a particularly challenging task: ‘it was not until the score had arrived’, he writes, ‘that I realized that this was actually a solo work, demanding the performer to play the oud and use his voice – singing in German and reciting in Arabic’. He goes on to comment that this task is ‘unusual and insecure’ but also has ‘desirable qualities, such as a certain directness and intimacy’. This is emphasised by the track ordering, the insecurity of the two part-time singers framing Zman-vertont (2007) in which Mikael Bellini’s thrillingly exact countertenor weaves around baroque oboe and violin lines.

Lipparella’s musicianship is consistently compelling: they have found their way into the heart of Zimmermann’s enigmatic, anti-rhetorical aesthetic and the performances and recordings have that ‘certain directness and intimacy’ that Söderberg mentions. Yet the music itself, for all its

textural and formal clarity, is rarely direct. The earliest work, Shadows of Cold Mountain 1 (1994), sounds straightforward enough: the music traces a single sliding line, but what is determining its path, and why is it being played simultaneously by three tenor blockflutes (here multitracked)? The answers are provided in Zimmermann’s contribution to the liner notes: the sliding line is a transcription of calligraphy from the ‘Cold Mountain’ series that Brice Marden (1938-2023) began in the mid-1980s and it is multitracked because the resultant interference tones draw together ‘the world of colour and the world of sound’.

Like all Walter Zimmermann’s work, the Chantbook for Lipparella maps an ocean of intertextual currents. His is music that has fascinated me ever since I first encountered it in 1982 but nowhere before have I found the paradox of its variety of means and unity of purpose so beautifully articulated as it is in this album. To quote Inger Christiansen’s words in Cirkel again, this is music that ‘sketches a spindly circle’ but, as it does so, also ‘puts a finger to the lips’ and ‘lays a hand on the heart’.

Christopher Fox